Historical roots and current state[edit | edit code]

How should an effective training process be planned for athletes? This is a question that has long occupied the thoughts of prominent scientists, analysts and practitioners. In the history of ancient medicine and philosophy there are facts concerning the formation and development of the theory of training. Indeed, the process of its formation dates back more than 2000 years and originates from famous ancient philosophers and doctors. Thus, the great thinkers of antiquity Galen and Philostratus can be considered the real harbingers of modern training theory. The ancient Roman philosopher and physician Galen (Claudius Aelius Galen - 2nd century AD) wrote a treatise “Maintaining Health”, where he examined various aspects of physical fitness.

Another example of outstanding creative thought is associated with the famous ancient Greek scientist Philostratus (of Athens), who lived in the 2nd century. AD Philostratus probably gave the first idea of the periodization of the training process. His memorable essay “On Gymnastics” contains a description of pre-Olympic preparation, which, in the author’s opinion, should contain such a mandatory component of the program as a ten-month period of focused training (Drees, 1968).

This basic stage was followed by one month of centralized preparation for the Olympic Games, which took place in the city of Alice. Apparently, the modern practice of pre-Olympic training camps dates back to that time (i.e. about 2000 years ago). Another proposal of Philostrat concerns the compilation of a short four-day training cycle (a sequence of small, medium and large loads), which was later called a microcycle

.

Research Review

. In the history of ancient medicine and philosophy one can find memorable milestones in the development of the theory of sports training. These fragments of human creativity are associated with the names of great ancient thinkers such as Galen and Philostratus. The famous Roman physician and philosopher Galen (Claudius Aelius Galen - 2nd century AD) in his treatise “Maintaining Health” proposed an original classification of exercises, which can be considered the predecessor of the modern periodization of strength training (Gardiner, 1930). The sequence of his exercises from “exercises with strength but without speed” to the development of “speed apart from strength” and finally to intense exercises combining strength and speed (Robinson, 1955) strikes us with its logic and creativity, although in light modern knowledge there may be questions about it. Another example of annual periodization can be found in the essay “On Gymnastics” by the outstanding ancient Greek scientist Philostratus of Athens, who lived in the 2nd century. AD (Drees, 1968). His description of pre-Olympic preparation contains a mandatory ten-month period of focused preparation, followed by a month of centralized training (in the city of Alice) before the start of the Olympic Games. This final part of the annual cycle is reminiscent of the pre-Olympic training camps practiced by any national team today. The guidelines established by Philostratus regarding the sequence of light, medium and heavy training loads within a four-day training cycle can serve as a brilliant illustration of the ancient approach to short-term planning.

The modern Olympic era has stimulated activities related to athletic training. Perhaps one of the first monographs dedicated to high-level sports training was published by Boris Kotov. His book “Olympic Sport” (1916) presented an original concept of periodization of training, which proposed three stages of targeted sports preparation for upcoming competitions: general preparatory, more specialized and specific.

Further development of the theoretical foundations of sports training was carried out by one of the founders of modern sports medicine, V.V. Gorinevsky (1922). His voluminous publication contained a rationale for targeted sports specialization and an explanation of the role of versatile athletic training as the main condition for effective training in a particular sport. Another prominent training analyst G.K. Birzin (1925) provided one of the first descriptions of the biological nature of athletic training, emphasizing the interaction between fatigue and recovery after exercise. The author outlined possible options for a rational sequence of physical activity and recovery after it.

The theoretical basis for the periodization of sports training was further developed in the important publications of Lauri Pihkala (1930), who postulated a number of principles, such as the division of the annual cycle into preparatory, spring and summer phases and active rest at the end of the season. He also introduced the principles of alternating extensive and intense exercise, focusing on the correct load-rest ratio, and the fundamentals of long-term athletic training.

The know-how of the 1930s was creatively adapted and interpreted in several books published in the USSR. These were serious textbooks for sports universities on skiing (Bergman, 1938), swimming (Shuvalov, 1940), and athletics (Vasiliev, Ozolin, 1952), which contained relevant chapters on training planning. There it was already divided into general and special; focused preparation for competition was described appropriately, with particular attention to physical, technical and mental factors.

Despite the fact that the theory of sports training already had a fairly long history, a real milestone in its creation was the monograph by Lev Pavlovich Matveev (1964), in which he summarized the available information on the training of athletes and proposed a general approach to planning. This eventually became known as the “classical” approach. At a time when the theory of sports training suffered from a lack of objective knowledge and scientifically based principles of training, the book by L.P. Matveeva became a real breakthrough in coaching science. Thus, the periodization model with a logical structuring of an athlete’s training and a clear hierarchy of training cycles and blocks has become a universal tool for planning and analyzing the training process in all sports for athletes of different skill levels. At the same time, this dominant concept spread throughout the world and appeared in the works of other authors such as Nagge (1973), Martin (1980), Bompa (1984), etc.

Historical roots and current state

How should an effective training process be planned for athletes? This is a question that has long occupied the thoughts of prominent scientists, analysts and practitioners. In the history of ancient medicine and philosophy there are facts concerning the formation and development of the theory of training. Indeed, the process of its formation dates back more than 2000 years and originates from famous ancient philosophers and doctors. Thus, the great thinkers of antiquity Galen and Philostratus can be considered the real harbingers of modern training theory. The ancient Roman philosopher and physician Galen (Claudius Aelius Galen - 2nd century AD) wrote a treatise “Maintaining Health”, where he examined various aspects of physical fitness.

Another example of outstanding creative thought is associated with the famous ancient Greek scientist Philostratus (of Athens), who lived in the 2nd century. AD Philostratus probably gave the first idea of the periodization of the training process. His memorable essay “On Gymnastics” contains a description of pre-Olympic preparation, which, in the author’s opinion, should contain such a mandatory component of the program as a ten-month period of focused training (Drees, 1968).

This basic stage was followed by one month of centralized preparation for the Olympic Games, which took place in the city of Alice. Apparently, the modern practice of pre-Olympic training camps dates back to that time (i.e. about 2000 years ago). Another proposal of Philostrat concerns the compilation of a short four-day training cycle (a sequence of small, medium and large loads), which was later called a microcycle

.

Research Review

. In the history of ancient medicine and philosophy one can find memorable milestones in the development of the theory of sports training. These fragments of human creativity are associated with the names of great ancient thinkers such as Galen and Philostratus. The famous Roman physician and philosopher Galen (Claudius Aelius Galen - 2nd century AD) in his treatise “Maintaining Health” proposed an original classification of exercises, which can be considered the predecessor of the modern periodization of strength training (Gardiner, 1930). The sequence of his exercises from “exercises with strength but without speed” to the development of “speed apart from strength” and finally to intense exercises combining strength and speed (Robinson, 1955) strikes us with its logic and creativity, although in light modern knowledge there may be questions about it. Another example of annual periodization can be found in the essay “On Gymnastics” by the outstanding ancient Greek scientist Philostratus of Athens, who lived in the 2nd century. AD (Drees, 1968). His description of pre-Olympic preparation contains a mandatory ten-month period of focused preparation, followed by a month of centralized training (in the city of Alice) before the start of the Olympic Games. This final part of the annual cycle is reminiscent of the pre-Olympic training camps practiced by any national team today. The guidelines established by Philostratus regarding the sequence of light, medium and heavy training loads within a four-day training cycle can serve as a brilliant illustration of the ancient approach to short-term planning.

The modern Olympic era has stimulated activities related to athletic training. Perhaps one of the first monographs dedicated to high-level sports training was published by Boris Kotov. His book “Olympic Sport” (1916) presented an original concept of periodization of training, which proposed three stages of targeted sports preparation for upcoming competitions: general preparatory, more specialized and specific.

Further development of the theoretical foundations of sports training was carried out by one of the founders of modern sports medicine, V.V. Gorinevsky (1922). His voluminous publication contained a rationale for targeted sports specialization and an explanation of the role of versatile athletic training as the main condition for effective training in a particular sport. Another prominent training analyst G.K. Birzin (1925) provided one of the first descriptions of the biological nature of athletic training, emphasizing the interaction between fatigue and recovery after exercise. The author outlined possible options for a rational sequence of physical activity and recovery after it.

The theoretical basis for the periodization of sports training was further developed in the important publications of Lauri Pihkala (1930), who postulated a number of principles, such as the division of the annual cycle into preparatory, spring and summer phases and active rest at the end of the season. He also introduced the principles of alternating extensive and intense exercise, focusing on the correct load-rest ratio, and the fundamentals of long-term athletic training.

The know-how of the 1930s was creatively adapted and interpreted in several books published in the USSR. These were serious textbooks for sports universities on skiing (Bergman, 1938), swimming (Shuvalov, 1940), and athletics (Vasiliev, Ozolin, 1952), which contained relevant chapters on training planning. There it was already divided into general and special; focused preparation for competition was described appropriately, with particular attention to physical, technical and mental factors.

Despite the fact that the theory of sports training already had a fairly long history, a real milestone in its creation was the monograph by Lev Pavlovich Matveev (1964), in which he summarized the available information on the training of athletes and proposed a general approach to planning. This eventually became known as the “classical” approach. At a time when the theory of sports training suffered from a lack of objective knowledge and scientifically based principles of training, the book by L.P. Matveeva became a real breakthrough in coaching science. Thus, the periodization model with a logical structuring of an athlete’s training and a clear hierarchy of training cycles and blocks has become a universal tool for planning and analyzing the training process in all sports for athletes of different skill levels. At the same time, this dominant concept spread throughout the world and appeared in the works of other authors such as Nagge (1973), Martin (1980), Bompa (1984), etc.

Basic provisions of the traditional theory[edit | edit code]

The cornerstones of the theory of sports training are the hierarchy of training cycles and the basics of periodization of training. This hierarchical system of training cycles, which are periodically repeated, is the central element of the training theory (Table 1). The top level of this hierarchical ladder is the four-year Olympic cycle, comparable to other great events in the world of sports. The next level is represented by macrocycles. The macrocycle usually lasts one year, but can be shortened to six months or more. Such flexibility in dividing the annual cycle is not related to the block approach to periodization. Macrocycles are divided into training periods. Preparation periods serve a key function in traditional theory because they divide the macrocycle into two main parts: the first for more general preliminary work (preparatory period) and the second for more sport-specific work in a specialized pre-competition period and participation in competition (competitive period). period).

In addition, there is a third (short) period, which is intended for active recovery and rehabilitation. The next two levels of the presented hierarchy are occupied by mesocycles (medium training cycles) and microcycles (short training cycles). The bottom rung of this hierarchical ladder belongs to training and exercises, which are the building blocks of the entire training system.

Table 1. Hierarchy and duration of training periods and cycles

| Training period | Duration | Planning method |

| Four-year (Olympic) cycle | Four years - the period between the Olympic Games | Long term |

| Macrocycle (possibly yearly) | One year or several months | |

| Mesocycle | Few weeks | Medium term |

| Microcycle | One week or several days | Short |

| Training | Several hours (usually no more than three) | |

| Training exercise | Minutes (usually) |

The periods of the training process provide sufficient freedom in its planning. External factors such as the competition calendar and seasonal changes dictate the presence of peak phases and possible restrictions. As a result, the trainer can choose the sequence, content and duration of training cycles and determine the specifics of means and methods for each of them.

In practice, the most important component of the presented hierarchical scheme is the structuring of the annual cycle. This component, as a rule, is considered to represent the actual periodization of the training process. The traditional approach points to the general characteristics of the relevant periods and divides them into several stages. The content of the training process of each stage is clearly determined by the volume and intensity of the load (Table 2).

Table 2. General characteristics of the periodization of the training process in the traditional approach (according to Matveev, 1977)

| Period | Stage | Goals | Training load |

| Preparatory | General preparatory | Increasing the level of development of general motor abilities. Expanding the range of different motor skills | Relatively high volume and reduced intensity of core exercises; wide variety of training tools |

| Specially preparatory | Increasing the level of special preparedness; improvement of more specialized motor and technical abilities | The volume of the training load reaches its maximum; intensity increases selectively | |

| Competitive | Competitive preparation | Improving special preparedness for the sport, technical and tactical skills; formation of individual schemes for successful performance of a competitive exercise | Stabilization and reduction of the training load volume simultaneously with an increase in the intensity of specific exercises for the sport |

| Direct pre-competition preparation | Achieving the best specific preparedness for the sport and readiness for the main competition | Small volumes, high intensity; the most accurate simulation of the upcoming competition | |

| Transition | Transition | Recovery | Leisure |

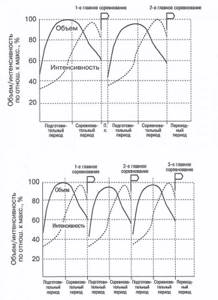

Initially, the traditional approach assumed one macrocycle per year, which was mainly associated with the practice of seasonal sports such as football, rowing, cycling, skiing, etc. Figure 3 shows an example of a typical single-cycle scheduling.

Rice. 3. Traditional representation of an annual training cycle with one macrocycle (annual periodization with one peak)

As noted, the single-peak annual cycle was particularly suitable for seasonal sports, but did not meet the requirements of those sports in which athletes competed at all times of the year and in each of them (like fencing, swimming, some doubles and team events). Later modifications allowed the use of two and three macrocycles within one annual cycle. Each macrocycle was divided into preparatory and competitive periods, which were characterized by certain combinations of training goals and loads. The transition period (of short duration) was included, for the most part, at the end of the season. This planning approach was called two- and three-peak annual periodization (Fig. 4).

Rice. 4. Representation of an annual cycle with two and three macrocycles (two- and three-peak annual periodization)

Mesocycles (training cycles of medium duration) have been interpreted in different ways. Most Eastern European authors proposed from seven to eleven types of mesocycles and systematized them in accordance with a number of conditions. One such classification is presented below (Table 3).

The classification presented above is the most concise compared to others. Despite the fact that various variants of mesocycle classifications look very informative, their practical implementation is limited by excessive detail and the artificial nature of differentiation.

Microcycles, as the shortest training cycles, have less controversy. Although there is no consensus among authors regarding the names of the various microcycles, the following summary table may help clarify the situation (Table 4).

Table 3. Types of mesocycles in accordance with the traditional approach to periodization of the training process

(after Zheliazkov, 1986)

| Name | Description |

| Retractor | Involves a gradual increase in load and adjustment to a more intense program. |

| Base | Involves performing the heaviest loads and lasts 4-6 weeks |

| Stabilization | Follows the baseline to stabilize the achieved level of preparedness |

| Pre-competition | Contains direct preparation for the upcoming competition |

| Competitive | Includes participation in the competition |

| Intermediate | Planned in case of a long competitive period to prevent excessive fatigue and prepare for further participation in the competition |

| Restorative | Characterized by reduced loads aimed at active recovery |

Table 4. Types of microcycles (according to various publications)

| Name | General characteristics |

| Tuning. retracting, initializing | Medium load level, gradual increase in training load |

| Load. developing, ordinary | Increased load level, use of large and significant training loads |

| Shock. shock, extreme loads | Using and imposing extreme training loads |

| Pre-competitive, tuning, peak | Average training loads, use of sport-specific means and methods |

| Competitive | Competitive exercises specific to the sport and sports discipline |

| Restorative. regenerating | Low level of training loads, use of a wide range of restorative agents |

* The underlined title corresponds to the version preferred by the author.

Basic provisions of traditional theory

The cornerstones of the theory of sports training are the hierarchy of training cycles and the basics of periodization of training. This hierarchical system of training cycles, which are periodically repeated, is the central element of the training theory (Table 1). The top level of this hierarchical ladder is the four-year Olympic cycle, comparable to other great events in the world of sports. The next level is represented by macrocycles. The macrocycle usually lasts one year, but can be shortened to six months or more. Such flexibility in dividing the annual cycle is not related to the block approach to periodization. Macrocycles are divided into training periods. Preparation periods serve a key function in traditional theory because they divide the macrocycle into two main parts: the first for more general preliminary work (preparatory period) and the second for more sport-specific work in a specialized pre-competition period and participation in competition (competitive period). period).

In addition, there is a third (short) period, which is intended for active recovery and rehabilitation. The next two levels of the presented hierarchy are occupied by mesocycles (medium training cycles) and microcycles (short training cycles). The bottom rung of this hierarchical ladder belongs to training and exercises, which are the building blocks of the entire training system.

Table 1. Hierarchy and duration of training periods and cycles

| Training period | Duration | Planning method |

| Four-year (Olympic) cycle | Four years - the period between the Olympic Games | Long term |

| Macrocycle (possibly yearly) | One year or several months | |

| Mesocycle | Few weeks | Medium term |

| Microcycle | One week or several days | Short |

| Training | Several hours (usually no more than three) | |

| Training exercise | Minutes (usually) |

The periods of the training process provide sufficient freedom in its planning. External factors such as the competition calendar and seasonal changes dictate the presence of peak phases and possible restrictions. As a result, the trainer can choose the sequence, content and duration of training cycles and determine the specifics of means and methods for each of them.

In practice, the most important component of the presented hierarchical scheme is the structuring of the annual cycle. This component, as a rule, is considered to represent the actual periodization of the training process. The traditional approach points to the general characteristics of the relevant periods and divides them into several stages. The content of the training process of each stage is clearly determined by the volume and intensity of the load (Table 2).

Table 2. General characteristics of the periodization of the training process in the traditional approach (according to Matveev, 1977)

| Period | Stage | Goals | Training load |

| Preparatory | General preparatory | Increasing the level of development of general motor abilities. Expanding the range of different motor skills | Relatively high volume and reduced intensity of core exercises; wide variety of training tools |

| Specially preparatory | Increasing the level of special preparedness; improvement of more specialized motor and technical abilities | The volume of the training load reaches its maximum; intensity increases selectively | |

| Competitive | Competitive preparation | Improving special preparedness for the sport, technical and tactical skills; formation of individual schemes for successful performance of a competitive exercise | Stabilization and reduction of the training load volume simultaneously with an increase in the intensity of specific exercises for the sport |

| Direct pre-competition preparation | Achieving the best specific preparedness for the sport and readiness for the main competition | Small volumes, high intensity; the most accurate simulation of the upcoming competition | |

| Transition | Transition | Recovery | Leisure |

Initially, the traditional approach assumed one macrocycle per year, which was mainly associated with the practice of seasonal sports such as football, rowing, cycling, skiing, etc. Figure 3 shows an example of a typical single-cycle scheduling.

Rice. 3. Traditional representation of an annual training cycle with one macrocycle (annual periodization with one peak)

As noted, the single-peak annual cycle was particularly suitable for seasonal sports, but did not meet the requirements of those sports in which athletes competed at all times of the year and in each of them (like fencing, swimming, some doubles and team events). Later modifications allowed the use of two and three macrocycles within one annual cycle. Each macrocycle was divided into preparatory and competitive periods, which were characterized by certain combinations of training goals and loads. The transition period (of short duration) was included, for the most part, at the end of the season. This planning approach was called two- and three-peak annual periodization (Fig. 4).

Rice. 4. Representation of an annual cycle with two and three macrocycles (two- and three-peak annual periodization)

Mesocycles (training cycles of medium duration) have been interpreted in different ways. Most Eastern European authors proposed from seven to eleven types of mesocycles and systematized them in accordance with a number of conditions. One such classification is presented below (Table 3).

The classification presented above is the most concise compared to others. Despite the fact that various variants of mesocycle classifications look very informative, their practical implementation is limited by excessive detail and the artificial nature of differentiation.

Microcycles, as the shortest training cycles, have less controversy. Although there is no consensus among authors regarding the names of the various microcycles, the following summary table may help clarify the situation (Table 4).

Table 3. Types of mesocycles in accordance with the traditional approach to periodization of the training process

(after Zheliazkov, 1986)

| Name | Description |

| Retractor | Involves a gradual increase in load and adjustment to a more intense program. |

| Base | Involves performing the heaviest loads and lasts 4-6 weeks |

| Stabilization | Follows the baseline to stabilize the achieved level of preparedness |

| Pre-competition | Contains direct preparation for the upcoming competition |

| Competitive | Includes participation in the competition |

| Intermediate | Planned in case of a long competitive period to prevent excessive fatigue and prepare for further participation in the competition |

| Restorative | Characterized by reduced loads aimed at active recovery |

Table 4. Types of microcycles (according to various publications)

| Name | General characteristics |

| Tuning. retracting, initializing | Medium load level, gradual increase in training load |

| Load. developing, ordinary | Increased load level, use of large and significant training loads |

| Shock. shock, extreme loads | Using and imposing extreme training loads |

| Pre-competitive, tuning, peak | Average training loads, use of sport-specific means and methods |

| Competitive | Competitive exercises specific to the sport and sports discipline |

| Restorative. regenerating | Low level of training loads, use of a wide range of restorative agents |

* The underlined title corresponds to the version preferred by the author.

Criticisms of traditional sports training theory[edit | edit code]

Traditional athletic training theory was formulated at a time when knowledge of the topic was limited and few scientifically based guidelines for athletic training existed. The traditional periodization of sports training, which absorbed the then-current know-how of the 1960s, was a real breakthrough in the training process and sports science. Many of its elements adopted then remain in force today, including the hierarchical taxonomy and terminology of training cycles; differentiation between general and special sports training; changes in exercise volume and intensity; main approaches to short-term, medium-term and long-term planning, etc. It would be unrealistic to expect that all the ideas proposed more than five decades ago would still be applicable today.

One more circumstance must be taken into account. As can be seen from the previous sections, the foundations of the traditional theory of sports training were formulated mainly in the USSR. At that time, this theory became universal and monopolized methodological approaches to any scientific research and training plans for athletes. This ideologically dependent atmosphere of discussion was not very conducive to the expression of critical opinions about the concept supported by the official authorities. However, in the late 1970s, criticism emerged. The main criticism was directed at the central idea of the theoretical concept - the periodization of the process of training athletes. Over time, effective examples of planning and designing training programs based on the traditional periodization scheme emerged, and its shortcomings were noted by both creative coaches and analysts. As a result, criticism began to be published from the late 1970s and continues to be published today (Table 5).

Table 5. Summary of the essence of criticisms of the traditional theory of periodization of sports training

| Source | Problems | Comments by V.B. Issurina |

| Vorobyov, 1977 | Increasing the volume of training loads to the maximum does not lead to the achievement of the best results. The principle of gradualism is not universal; the load can change abruptly. Long-term, low-intensity training in the preparatory period reduces the effect of the entire season's training. The concept of general physical training needs to be revised to take into account the morphological and functional requirements for the athlete | The trend towards maximizing the volume of training was typical of the training of athletes at that time. A gradual increase in load was considered a fundamental condition in planning. The relatively long preparatory program did not adapt the athletes to the specific requirements of competitive activity. Basic physical training should be less generalized and more specific to the sport |

| Bondarchuk, 1986 | A large amount of work with low intensity in the preparatory period is useless. The duration of the preparatory period is variable and depends on individual requirements and the specifics of competitive activity. Wave changes in the volume and intensity of the training load cannot be considered a universal scheme. General physical training means do not form the basis for achieving readiness in a specific sport | This point of view is based mainly on the experience of speed-strength sports. The author claimed that the process of achieving athletic shape lasts from 2 to 8 months. In fact, both uniform and variable changes in training loads can be successfully implemented. The author did not find a positive transfer of the results of general preparatory exercises to sport-specific motor abilities |

| Tschiene, 1991 | The theory of sports training must postulate the primacy of the biological bases that explain functional adaptation and training transfer | The author presented a hierarchical diagram of the components of the theory of disputes. active training, the top level of which is occupied by Anokhin’s theory of functional systems |

| Zanon, 1997 | The theory of sports training has time limitations and needs to be updated taking into account new results | This theory has no scientific evidence to support its dominant role in athlete training. |

| Verkhoshansky, 1998 | Traditional theory is not based on the biological nature of sports training and even ignores it. The fundamental tenets of this theory are not supported by evidence drawn from coaching experience and research. The theory proposes to regulate the training impact using only manipulations with the volume of the load and its intensity. | Classical explanations relied exclusively on pedagogical arguments and definitions. The author showed the non-specific and abstract nature of theoretical positions and statements. Features and specifics of physiological adaptation were not taken into account |

| Issurin, 2002; Issurin, 2008 | The simultaneous development of a number of sports abilities leads to conflicting physiological reactions and reduces the effectiveness of training. Excessively long periods of low-intensity basic training do not provide sufficient training impact. The traditional model does not allow for a multi-peak competitive period | It is impossible to ensure a high concentration of properly directed loads and optimal interaction of incompatible training means. Long preparatory periods weaken the response to training load, reduce the rate of sports improvement and prevent the opportunity to take part in many competitions |

The periodization of sports training has not often become the object of particularly harsh criticism from analysts and coaches. In general, periodization makes use of periodic changes in human biological and social activity. For a long time, this theory has been accepted as a universal basis for the training process in any sport and for athletes of any skill level. In fact, the practice of training high-level athletes provided evidence that this theory does not provide universal tools for planning training or its implementation. Namely, A.N. Vorobyov, an internationally recognized expert in weightlifting and a former Olympic champion, identified serious contradictions between traditional theory and the realities of training elite athletes by analyzing data obtained during the training of weightlifters (Vorobyov, 1977). His harsh criticism was based on conclusions drawn after extensive and in-depth research, as well as on serious factors of the biological nature of the athlete’s body’s adaptation to training loads.

In the same way A.P. Bondarchuk, a world-famous authority in coaching science and a former Olympic champion in hammer throwing, noted the inconsistency of the theoretical principles and practice of training athletes in athletics. His criticisms were supported by his vast experience in training elite athletes and the results of his own research (Bondarchuk, 1986).

Sports training specialists from Germany (Tschiene, 1991) and Italy (Zanon, 1997) noted the inconsistency of traditional theory, based on updated scientific and methodological information. They also noted that each theory may have time limitations and its updating should be considered a reasonable and natural trend.

Somewhat later Yu.V. Verkhoshansky (1998) has become one of the harshest critics of traditional theory, emphasizing its overly scholastic nature, ignorance of the biological nature of training, lack of specific guiding principles for coaching, and contradictions between the proposed theoretical positions and the realities of modern sport.

Critical arguments in my own publications (Issurin, 2002; Issurin, 2008) were related to the shortcomings of the concept of traditional periodization of the training process for highly qualified athletes. My own experiences and research have come from conducting research in kayaking, canoeing, swimming and rowing. The most important criticisms have been related to the emergence of conflicting physiological responses when athletes work on many athletic abilities at the same time. For example, the training process of highly qualified athletes in endurance sports, martial arts, pairs and team sports, as well as artistic sports in the preparatory period involves the development of general aerobic abilities, muscle strength, strength endurance, improvement of general coordination and explosive strength, basic psychological and technical training, mastering tactical skills and treating injuries. Each of these factors requires special physiological, morphological and psychological adaptation. However, many workloads are incompatible and cause conflicting physiological responses. The causes and consequences of these contradictory reactions are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6. The main reasons for conflicting physiological reactions that arise during the training of high-level athletes using the traditional approach to planning

(Issurin, 2007)

| Factors | Controversies | Consequences |

| Energy supply | There are no adequate energy sources to simultaneously perform a variety of training loads | Energy is directed towards achieving many goals, but the main one does not receive adequate energy support |

| Recovery various physiological systems | Due to different recovery periods for various physiological systems, athletes do not achieve a sufficient level of recovery | Athletes get tired and cannot concentrate all their efforts on achieving their main goals |

| Compatibility of various loads | Different exercises often interact negatively due to lack of energy supply, technical difficulty and/or neuromuscular fatigue | The use of certain loads eliminates or reduces the effect of previous or subsequent training |

| Mental concentration | Stressful loads require a high level of mental concentration, which cannot be extended to many goals at the same time | It is difficult to maintain mental concentration, so exercises are performed with reduced attention and motivation |

| Training Stimuli for Athletes' Progression | The sport-specific progression of high-level athletes requires a high concentration of training stimuli, which cannot be achieved by simultaneously training many qualities | The simultaneous comprehensive development of many qualities does not provide a sufficient improvement in the level of preparedness of highly qualified athletes |

The limitations of the traditional training model mentioned above have been tested by many trainers, but not all of them have been critically evaluated. The most prominent trainers have come to the conclusion that the usual schemes for using highly effective stimulating loads must be revised. They found that the problem with training high-level athletes is that their progress requires large, highly concentrated workloads that cannot achieve many different goals simultaneously.

Another reason for criticism of the traditional periodization model lies in the inability to provide multi-peak competitive training throughout the season.

Example

.

Data from three world-class athletes - Marion Jones (USA), Sergei Bubka (Soviet Union, Ukraine since 1991) and Stefka Kostadinova (Bulgaria) show that pre-season and season training for each of them lasts about 300-320 days (Table 10) .

As can be seen from the table, the periods of time in which these athletes competed and demonstrated peak performance and when they had relatively high performance ranged from 135 to 265 days. Such a long period of time cannot be divided into traditional preparatory and competitive periods. On the other hand, the basic abilities of these athletes (maximum strength, aerobic energy production capacity) must be maintained at a fairly high level for 5-8 months. Therefore, the training program must include appropriate training cycles to improve basic abilities and recovery. The traditional design does not solve this problem and is unable to provide such training as part of the basic plan. Table 7. Multi-peak annual training of world-class athletes

(after Suslov, 2001; modification by the author)

| Athlete, events, best achievements | Year | Number of peaks per season | Typical Peak Intervals (days) | Duration of the competition period (days) |

| Marion Jones; running 100-200 m, long jump; 3-time Olympic champion in 2000, 5-time world champion | 1998 | 10* | 19-22 | 200 |

| Sergey Bubka; pole vault; Olympic champion in 1988, 5-time world champion, world record holder | 1991 | 7** | 23-43 | 265 |

| Stefka Kostadinova; High jump; 1996 Olympic champion, 2-time world champion, world record holder | 1998 | -11*** | 14-25 | In winter - 20; in the spring and in summer - 135 |

* There were eight competitive peaks in running and two separate peaks in long jump; all peaks are at the level of best personal results; ** All peaks are within 3% of his personal best result, namely 595-612 cm; *** All peaks are within 3% of her best personal result, namely 200-205 cm

Bearing in mind all the critical arguments and comments presented above, we can conclude that the realities of elite sports provide sufficient grounds for revising some of the provisions of the traditional theory of sports training and searching for alternative models and concepts.

Criticisms of Traditional Sports Training Theory

Traditional athletic training theory was formulated at a time when knowledge of the topic was limited and few scientifically based guidelines for athletic training existed. The traditional periodization of sports training, which absorbed the then-current know-how of the 1960s, was a real breakthrough in the training process and sports science. Many of its elements adopted then remain in force today, including the hierarchical taxonomy and terminology of training cycles; differentiation between general and special sports training; changes in exercise volume and intensity; main approaches to short-term, medium-term and long-term planning, etc. It would be unrealistic to expect that all the ideas proposed more than five decades ago would still be applicable today.

One more circumstance must be taken into account. As can be seen from the previous sections, the foundations of the traditional theory of sports training were formulated mainly in the USSR. At that time, this theory became universal and monopolized methodological approaches to any scientific research and training plans for athletes. This ideologically dependent atmosphere of discussion was not very conducive to the expression of critical opinions about the concept supported by the official authorities. However, in the late 1970s, criticism emerged. The main criticism was directed at the central idea of the theoretical concept - the periodization of the process of training athletes. Over time, effective examples of planning and designing training programs based on the traditional periodization scheme emerged, and its shortcomings were noted by both creative coaches and analysts. As a result, criticism began to be published from the late 1970s and continues to be published today (Table 5).

Table 5. Summary of the essence of criticisms of the traditional theory of periodization of sports training

| Source | Problems | Comments by V.B. Issurina |

| Vorobyov, 1977 | Increasing the volume of training loads to the maximum does not lead to the achievement of the best results. The principle of gradualism is not universal; the load can change abruptly. Long-term, low-intensity training in the preparatory period reduces the effect of the entire season's training. The concept of general physical training needs to be revised to take into account the morphological and functional requirements for the athlete | The trend towards maximizing the volume of training was typical of the training of athletes at that time. A gradual increase in load was considered a fundamental condition in planning. The relatively long preparatory program did not adapt the athletes to the specific requirements of competitive activity. Basic physical training should be less generalized and more specific to the sport |

| Bondarchuk, 1986 | A large amount of work with low intensity in the preparatory period is useless. The duration of the preparatory period is variable and depends on individual requirements and the specifics of competitive activity. Wave changes in the volume and intensity of the training load cannot be considered a universal scheme. General physical training means do not form the basis for achieving readiness in a specific sport | This point of view is based mainly on the experience of speed-strength sports. The author claimed that the process of achieving athletic shape lasts from 2 to 8 months. In fact, both uniform and variable changes in training loads can be successfully implemented. The author did not find a positive transfer of the results of general preparatory exercises to sport-specific motor abilities |

| Tschiene, 1991 | The theory of sports training must postulate the primacy of the biological bases that explain functional adaptation and training transfer | The author presented a hierarchical diagram of the components of the theory of disputes. active training, the top level of which is occupied by Anokhin’s theory of functional systems |

| Zanon, 1997 | The theory of sports training has time limitations and needs to be updated taking into account new results | This theory has no scientific evidence to support its dominant role in athlete training. |

| Verkhoshansky, 1998 | Traditional theory is not based on the biological nature of sports training and even ignores it. The fundamental tenets of this theory are not supported by evidence drawn from coaching experience and research. The theory proposes to regulate the training impact using only manipulations with the volume of the load and its intensity. | Classical explanations relied exclusively on pedagogical arguments and definitions. The author showed the non-specific and abstract nature of theoretical positions and statements. Features and specifics of physiological adaptation were not taken into account |

| Issurin, 2002; Issurin, 2008 | The simultaneous development of a number of sports abilities leads to conflicting physiological reactions and reduces the effectiveness of training. Excessively long periods of low-intensity basic training do not provide sufficient training impact. The traditional model does not allow for a multi-peak competitive period | It is impossible to ensure a high concentration of properly directed loads and optimal interaction of incompatible training means. Long preparatory periods weaken the response to training load, reduce the rate of sports improvement and prevent the opportunity to take part in many competitions |

The periodization of sports training has not often become the object of particularly harsh criticism from analysts and coaches. In general, periodization makes use of periodic changes in human biological and social activity. For a long time, this theory has been accepted as a universal basis for the training process in any sport and for athletes of any skill level. In fact, the practice of training high-level athletes provided evidence that this theory does not provide universal tools for planning training or its implementation. Namely, A.N. Vorobyov, an internationally recognized expert in weightlifting and a former Olympic champion, identified serious contradictions between traditional theory and the realities of training elite athletes by analyzing data obtained during the training of weightlifters (Vorobyov, 1977). His harsh criticism was based on conclusions drawn after extensive and in-depth research, as well as on serious factors of the biological nature of the athlete’s body’s adaptation to training loads.

In the same way A.P. Bondarchuk, a world-famous authority in coaching science and a former Olympic champion in hammer throwing, noted the inconsistency of the theoretical principles and practice of training athletes in athletics. His criticisms were supported by his vast experience in training elite athletes and the results of his own research (Bondarchuk, 1986).

Sports training specialists from Germany (Tschiene, 1991) and Italy (Zanon, 1997) noted the inconsistency of traditional theory, based on updated scientific and methodological information. They also noted that each theory may have time limitations and its updating should be considered a reasonable and natural trend.

Somewhat later Yu.V. Verkhoshansky (1998) has become one of the harshest critics of traditional theory, emphasizing its overly scholastic nature, ignorance of the biological nature of training, lack of specific guiding principles for coaching, and contradictions between the proposed theoretical positions and the realities of modern sport.

Critical arguments in my own publications (Issurin, 2002; Issurin, 2008) were related to the shortcomings of the concept of traditional periodization of the training process for highly qualified athletes. My own experiences and research have come from conducting research in kayaking, canoeing, swimming and rowing. The most important criticisms have been related to the emergence of conflicting physiological responses when athletes work on many athletic abilities at the same time. For example, the training process of highly qualified athletes in endurance sports, martial arts, pairs and team sports, as well as artistic sports in the preparatory period involves the development of general aerobic abilities, muscle strength, strength endurance, improvement of general coordination and explosive strength, basic psychological and technical training, mastering tactical skills and treating injuries. Each of these factors requires special physiological, morphological and psychological adaptation. However, many workloads are incompatible and cause conflicting physiological responses. The causes and consequences of these contradictory reactions are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6. The main reasons for conflicting physiological reactions that arise during the training of high-level athletes using the traditional approach to planning

(Issurin, 2007)

| Factors | Controversies | Consequences |

| Energy supply | There are no adequate energy sources to simultaneously perform a variety of training loads | Energy is directed towards achieving many goals, but the main one does not receive adequate energy support |

| Recovery various physiological systems | Due to different recovery periods for various physiological systems, athletes do not achieve a sufficient level of recovery | Athletes get tired and cannot concentrate all their efforts on achieving their main goals |

| Compatibility of various loads | Different exercises often interact negatively due to lack of energy supply, technical difficulty and/or neuromuscular fatigue | The use of certain loads eliminates or reduces the effect of previous or subsequent training |

| Mental concentration | Stressful loads require a high level of mental concentration, which cannot be extended to many goals at the same time | It is difficult to maintain mental concentration, so exercises are performed with reduced attention and motivation |

| Training Stimuli for Athletes' Progression | The sport-specific progression of high-level athletes requires a high concentration of training stimuli, which cannot be achieved by simultaneously training many qualities | The simultaneous comprehensive development of many qualities does not provide a sufficient improvement in the level of preparedness of highly qualified athletes |

The limitations of the traditional training model mentioned above have been tested by many trainers, but not all of them have been critically evaluated. The most prominent trainers have come to the conclusion that the usual schemes for using highly effective stimulating loads must be revised. They found that the problem with training high-level athletes is that their progress requires large, highly concentrated workloads that cannot achieve many different goals simultaneously.

Another reason for criticism of the traditional periodization model lies in the inability to provide multi-peak competitive training throughout the season.

Example

.

Data from three world-class athletes - Marion Jones (USA), Sergei Bubka (Soviet Union, Ukraine since 1991) and Stefka Kostadinova (Bulgaria) show that pre-season and season training for each of them lasts about 300-320 days (Table 10) .

As can be seen from the table, the periods of time in which these athletes competed and demonstrated peak performance and when they had relatively high performance ranged from 135 to 265 days. Such a long period of time cannot be divided into traditional preparatory and competitive periods. On the other hand, the basic abilities of these athletes (maximum strength, aerobic energy production capacity) must be maintained at a fairly high level for 5-8 months. Therefore, the training program must include appropriate training cycles to improve basic abilities and recovery. The traditional design does not solve this problem and is unable to provide such training as part of the basic plan. Table 7. Multi-peak annual training of world-class athletes

(after Suslov, 2001; modification by the author)

| Athlete, events, best achievements | Year | Number of peaks per season | Typical Peak Intervals (days) | Duration of the competition period (days) |

| Marion Jones; running 100-200 m, long jump; 3-time Olympic champion in 2000, 5-time world champion | 1998 | 10* | 19-22 | 200 |

| Sergey Bubka; pole vault; Olympic champion in 1988, 5-time world champion, world record holder | 1991 | 7** | 23-43 | 265 |

| Stefka Kostadinova; High jump; 1996 Olympic champion, 2-time world champion, world record holder | 1998 | -11*** | 14-25 | In winter - 20; in the spring and in summer - 135 |

* There were eight competitive peaks in running and two separate peaks in long jump; all peaks are at the level of best personal results; ** All peaks are within 3% of his personal best result, namely 595-612 cm; *** All peaks are within 3% of her best personal result, namely 200-205 cm

Bearing in mind all the critical arguments and comments presented above, we can conclude that the realities of elite sports provide sufficient grounds for revising some of the provisions of the traditional theory of sports training and searching for alternative models and concepts.

Read also[edit | edit code]

- Sports training

- Goals and objectives of sports training

- Sports training

- Sports training methods

- Principles of Sports Training

- Training effects

- Trainability and heredity of athletes

- Transfer of training

- Training cycles (periodization of load and rest)

- Planning the training process General and special physical training

- Concentrated One-Directional Training Model

- Multi-objective block periodization model

Literature[edit | edit code]

- Bergman, B.I. (1940). Skiing. Textbook for physical education institutes. Moscow: publishing house FiS.

- Birzin, G.K. (1940). The essence of training. Moscow, Works on physical culture. Ed. 1, 2 and 5.

- Bompa, T. (1984). Theory and methodology of training - The key to athletic performance. Boca Raton, FL: Kendall/Hunt.

- Bondarchuk, A.P. (1986). Track and field athlete training. Kyiv: Health.

- Drees, L. (1968). Olympia, gods, artists and athletes. New York: Praeger.

- Gardiner, N. E. (1930). Athletics of the ancient world. Oxford:University Press.

- Issurin, V.B. (2002). The concept of block composition in the training of high-class athletes. Theory and practice of physical culture (Moscow); 5:2-5.

- Issurin, V. (2008). Block periodization vs. traditional training theory. A review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness; 48(1): 65-75.

- Kotov, B.A. (1916). Olympic sport. Basics of athletics. St. Petersburg: Maytov Publishing House.

- Martin, D. (1980). Grundlagen der Trainingslehre. Schorndorf: Verlag Karl Floffmann.

- Matveev, L.P. (1964). The problem of periodization of sports training. Moscow: publishing house FiS.

- Matveev, L.P. (1977). Basics of sports training. Moscow: Progress Publishing House.

- Pihkala, L. (1930). Allgemeine Richtlinien fur das athletics Training. In G. Kriimmel (Editor), Athletik Handbuch der lebenswichtigen Leibesiibungen. Miinchen: Lehmann; (pp. 185-198).

- Robinson, R. S. (1955). Sources for the history of Greek athletics. Chicago: Ares Publisher.

- Shuvalov, V.I. (1940). Swimming, water polo and diving. Textbook for physical education institutes. Moscow: publishing house FiS.

- Suslov, F. P. (2001). Annual training programs and the sport specific fitness levels of world class athletes. In: Annual Training Plans and the Sport Specific Fitness Levels of World Class Athletes, https:// www.coachr.org/annual_training_programmes.htm

- Tschiene, P. (1991). Die Prioritat des biologischen Aspects in der “Theorie des Trainings”; Leistundss-port, 6: 5-9.

- Vasiliev, G.V., Ozolin, N.G. (1952). Athletics. Textbook for physical education institutes. Moscow: publishing house FiS.

- Verkhoshansky, Yu.V. (1998). On the way to scientific theory and methodology of sports training. Theory and practice of physical culture (Moscow); 2: 21-41.

- Vorobyov, A.N. (1977). Weightlifting. Essays on physiology and sports training. Moscow: publishing house FiS.

- Zanon, S. (1997). Die alte “Theorie des Trainings” in der Kritik. Leistundssport; 3: 18-19.

- Zheliazkov, T. (1986). Theory and methodology of sport training. Sofia: Medicina i Phizcultura.